Why Education Supercharges Green Innovation

Published:

The climate debate is filled with talk of breakthrough technologies—solar panels, carbon capture, electric vehicles. These innovations are vital, but new machines alone won’t solve the problem. The real engine of climate progress may be something far less tangible: education.

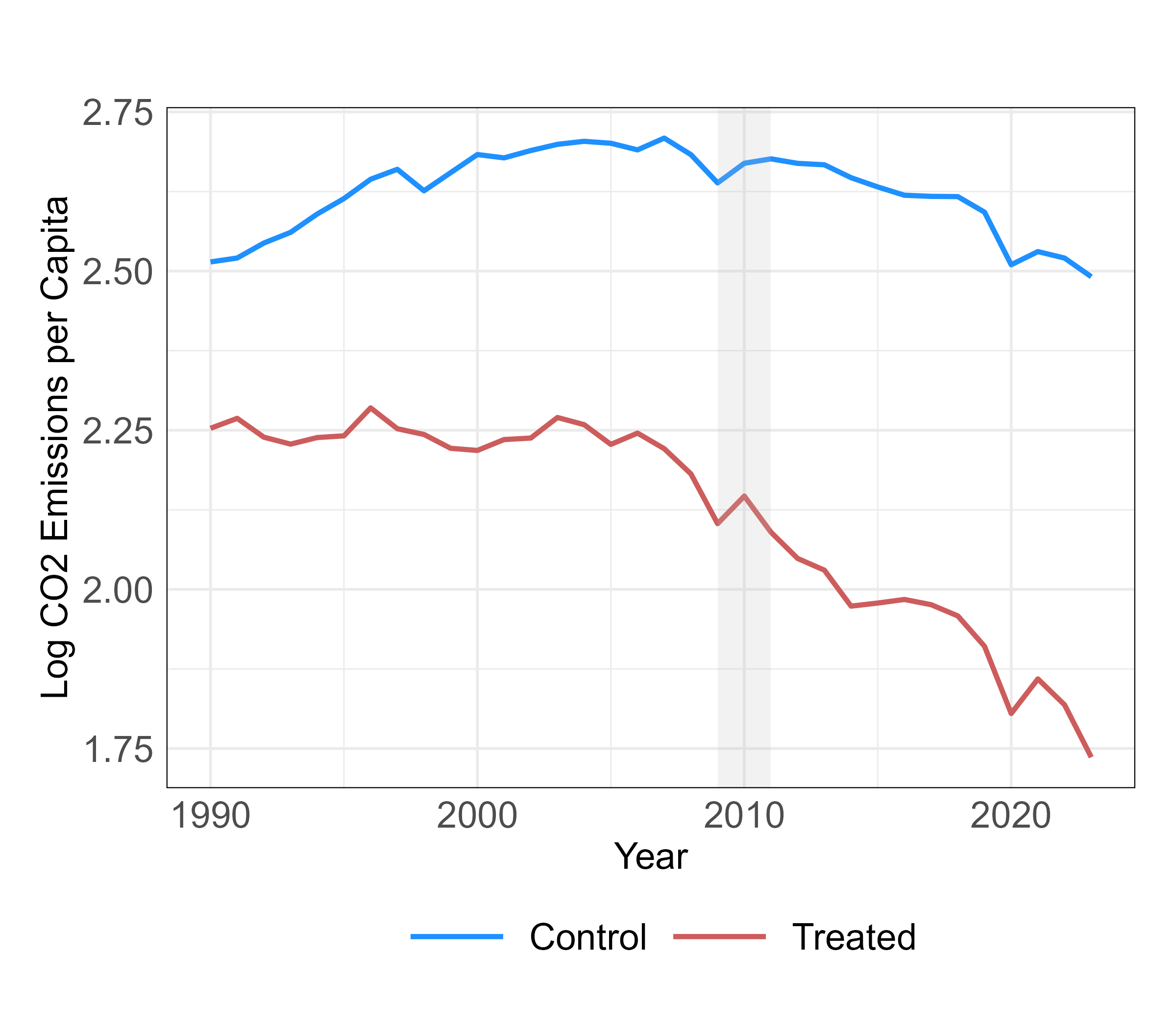

A recent study by Fernando Loaiza (The Complementary Role of Human Capital in Innovation-Driven Decarbonization, 2025) highlights a striking point: education and R&D are far more powerful together than apart. The findings show that human capital is not just an enabler of innovation—it is a climate solution in its own right.

The Numbers: Education as a Multiplier

The research shows that investing in R&D alone reduces CO₂ emissions by about 4.9%. That’s not trivial. But when higher levels of tertiary education are added into the mix, the reduction grows to 6.4%—a 30% stronger effect.

Think of it this way: every dollar invested in R&D goes further in a society where people are better educated. More scientists, engineers, and technically skilled workers mean faster adoption of green technologies, smarter innovations, and a stronger culture of sustainability. Education doesn’t just complement R&D; it multiplies its effect.

These findings also reveal that this education-innovation synergy plays out very differently across the world.

Why It Matters for Middle-Income Countries

Surprisingly, the biggest gains appear in middle-income economies. In these countries, education and R&D together cut emissions by about 14%—nearly triple the effect seen in richer economies.

Why such a large effect? Because middle-income countries are at a stage where they can leapfrog into cleaner growth paths. They are less locked into old, high-carbon infrastructures than industrialized economies, but they still need the human capital to absorb and apply new technologies. Education provides that bridge.

This has enormous implications for global climate finance and development cooperation. Donors and multilateral institutions often channel funds into hardware—solar parks, wind turbines, grid upgrades. But without investments in universities, vocational training, and workforce development, the potential of these technologies remains underutilized. For middle-income economies especially, education may be the single most important enabler of rapid decarbonization.

Limits in High-Emission Economies

The picture is different in the highest-emitting countries. Here, the education–R&D synergy is weaker. Structural challenges—like entrenched fossil fuel dependence, political resistance, and weaker governance—can blunt the benefits of human capital.

In these contexts, simply educating more engineers is not enough. Political will, regulatory enforcement, and institutional reform become decisive. Education can equip societies with the skills to act, but without enabling conditions, the impact is constrained. This finding is a reminder that technology and education must be matched by governance capacity and accountability if decarbonization is to succeed.

Beyond Innovation: Institutions and Efficiency

Loaiza’s research also points to broader pathways where education and R&D shape emissions reductions. Countries with stronger education systems show better policy enforcement, more effective energy efficiency, and lower carbon intensity—they emit less CO₂ per unit of GDP.

This matters because energy efficiency is often described as the “first fuel” of the transition. Technologies that reduce energy waste exist, but they only deliver results if industries and households know how to implement them. Education ensures that new knowledge is not just produced but actually embedded into economic systems.

At the same time, the study cautions that while education and R&D contribute to the growth of green jobs, these jobs don’t automatically reduce emissions. What matters is their type and scope—whether they contribute directly to decarbonization or only indirectly support the green transition. For policymakers, this is a reminder to align labor market policies with climate goals, not just count green jobs as successes.

Policy Implications: Making Human Capital a Climate Strategy

For organizations like the World Resources Institute, Stockholm Environment Institute, or UN agencies, these findings reinforce an urgent lesson: education policy is climate policy. Building human capital must be recognized as a pillar of decarbonization strategies, alongside finance, technology, and governance.

This means:

- Climate finance with a human capital lens: Development banks and donors should tie clean energy investments to support for education and training programs, especially in middle-income countries where the payoff is highest.

- Integrating education into industrial policy: Efforts like the EU’s Green Deal or the Just Transition Mechanism should view training and tertiary education not as side benefits, but as central to achieving emissions reductions.

- Empowering institutions through knowledge: Universities, vocational schools, and technical institutes are critical infrastructure for climate action. Strengthening them creates ripple effects across governance, industry, and society.

In global negotiations, from the UNFCCC to G20 meetings, there is growing recognition that climate solutions must be systemic. Education is one of the most under-acknowledged levers. By framing it not only as a development goal (SDG 4) but also as a decarbonization tool, policymakers can unlock synergies across the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Takeaway

The fight against climate change is not just about inventing new technologies—it’s about making sure societies are ready to harness them. Education isn’t a side issue. It’s a climate solution.

If we want R&D to deliver on its promise, classrooms, universities, and training programs must work hand in hand with labs and startups. Innovation may invent the tools, but education gives us the hands to use them.